State governments across the United States are looking to address the challenge to create more workforce housing to meet the rising demand in rural and urban markets. Housing and economic development professionals agree that new housing permits should be created on a 1:1 basis with the creation of net, new jobs. Failure to meet this demand creates rising costs as booming regions like Austin and others are enduring. These rising costs simply cannot be met by area residents often even making over $100,000. A range of state government tools have been created to support the development of more workforce housing.

ARPA Funding. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding from the federal government can be a major source of funding to spur housing development. The state of Michigan offers an interesting example of how ARPA funding can help address the housing challenge in a major Midwest Industrial State. The Michigan Missing Middle Housing Program is a housing production program designed to address the general lack of attainable housing and housing challenges underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic by increasing the supply of housing stock to support the growth and economic mobility of employees by providing cost defrayment to developers investing in, constructing, or substantially rehabbing properties targeted to household incomes between 185% and 300% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines (FPG). The Michigan Missing Middle Housing Program is funded by State appropriated ARPA Funds from the U.S. Department of the Treasury. $50 M of ARPA funding has been dedicated to the Missing Middle Housing Program. Missing Middle Grants are designed to help fill construction costs by funding gaps in eligible projects and are calculated using a formula-driven approach based on the number of Missing Middle units in the project. Eligible developments for this program include: new construction, adaptive re-use, or substantial rehabilitation (or combination thereof) with substantial rehabilitation is defined as rehabilitation of a housing unit that becomes an energy efficient housing unit and that requires financial investment of at least $25,000, rental housing or for-sale housing (or combination thereof, and multifamily attached, detached homes, or townhomes.

The largest driver of affordable housing development nationally is the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, a bipartisan public policy incentive that has driven outcomes through private sector investment and development. In Ohio, more than 100,000 affordable housing units have been developed through the federal LIHTC program. The federal LIHTC comes in two forms: the 9% and 4% credit. Projects utilizing the 4% credit are financed in part with tax-exempt bonds. Each year, $120 M of federal bond volume cap is allocated to Ohio for multifamily development, but a lack of additional leveraging funds has left this substantial federal resource untapped to Ohioans since 2015. In order to change this, additional funding sources like the state credit would leverage this substantial federal resource to the tune of $200-300 M and generate even more viable affordable housing development and economic impact in our state. Housing and business leaders in Ohio have joined together to seek additional ARPA funds for affordable housing. The U.S. Department of Treasury recently issued guidance that eliminates all remaining barriers to investing ARPA funds in affordable housing development and rehabilitation by:

• Clarifying that ARPA funds can be used to finance, develop, repair, or operate any

rental unit that provides affordability of 20 years or more to households at or below 65%

of local median income;

• Expanding presumptively eligible uses for affordable housing, and

• Increasing flexibility to use ARPA funds to fully finance long-term affordable housing

loans.

The Ohio Coalition on Homelessness and Housing and a group of housing and business trade associations are advocating that $308 M in ARPA funding be used to promote the development of affordable housing.

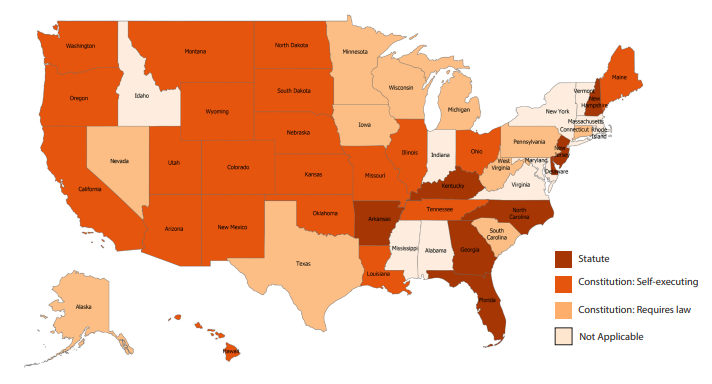

Infrastructure Funding. The provision of public infrastructure is a critical step to the development of workforce housing. Tax Increment Financing (TIF) is the most popular tool for local governments to finance public improvements within their districts or areas. TIFs started in California in the 1950s, and today, the District of Columbia and all of the states, other than Arizona, have adopted some form of TIF program.[i] Local government pays for public improvements and infrastructure by capturing the future tax increments from the project’s area under a TIF.[ii] The local government issues bonds to finance the project, and the bonds are paid for later through the increase in taxable property value the improved area receives.[iii] This increase in taxable property value is the “tax increment,” and it goes directly toward repaying the debt incurred by the local government on the issued bonds.[iv] TIF does not require an increase in taxes or a new tax levy. TIFs must provide an assured level of tax gains to provide the funding needed for the infrastructure planned. The crux of a TIF is the actual financing mechanism itself. Once a TIF project or district is approved, the local government can start collecting certain taxes from the project area. Generally, property taxes are the type collected, but a few states allow for other taxes, like sales taxes, to be included in the collection.[v] The taxes are then placed in a special fund, which reimburses the principal and the interest of the issued bonds.[vi] Once the value of the property increases, the gain in the taxable value goes to the local government to repay the debt incurred by the issued bonds. Thus, if the process works as planned, the project is self-sustaining and provides a benefit to the community without any new or increased taxes. States like Ohio and others permit the use of TIFs for residential development and this tool is critical to the development of public infrastructure including parking structures for many projects.

In addition to state TIF programs, funding for housing related infrastructure could be provided by replicating programs often used for developing industrial sites. Ohio’s Rural Industrial Loan Program could be mimicked to create the Ohio Rural Residential Loan Program and funding could be provided for rural based residential projects to gain the critical infrastructure they need. Ohio’s Transportation Improvement Districts could be mimicked as well to create Residential Improvement Districts with funding allocated from the state to funding infrastructure for workforce housing projects throughout Ohio.

Land Use Reform. State governments either regulate land use and other local governments through the Dillion Rule or Home Rule state constitutional models. The Dillon Rule is the principal that local government only exercises (1) powers expressly granted by the state, (2) powers necessarily and implied from the grant of power, and (3) powers crucial to the existence of local government. The Dillon Rule is named after Iowa Supreme Court Justice John F. Dillon and is based on a municipal philosophy he expressed in an 1868 case.1 In the court opinion, Justice Dillon emphasized that local governments are considered an extension of the

state and power is distributed to those local governments according to the state constitution. This philosophy was later reiterated by the United States Supreme Court in 1907 and became the guiding principles of local governments across the country. Home Rule is granted by state constitution or state statute and allocates some autonomy to a local government if the local government accepts certain conditions. Home Rule implies that each level of government has a separate realm of authority. Therefore, state power should not infringe on the authority of local government in certain areas. Often, local governments initiate this doctrine through an organizational plan called a Home Rule Charter that is adopted by a popular vote of the people. States using the Dillon Rule can define a streamlined land use zoning process that limits the timeframe and sets up a process by which residential development can be approved for zoning changes in urban and rural areas. However, states like Ohio that follow the Home Rule model can likely only impact this process through the adoption of land use regulations for rural townships as many cities and urban townships adopt charters that provide them Home Rule authority. However, states like Ohio could change the current rural township zoning model that centralizes this process with the County Commissioners and creates a simpler process for the approval of residential and other development.

Property Tax Abatements. A region’s property tax rates can directly impact their ability to retain and attract industrial, logistics, data centers and other capital-intensive corporate site location projects that can produce thousands of jobs in a post COVID 19 marketplaces. To address high property tax rates, most states across the United States permit local cities, townships, and counties to adopt property tax abatements tied to capital investment and payroll creation. One of those programs is the Ohio Community Reinvestment Area (CRA) program, which is an economic development tool administered by municipal and county government that provides real property tax exemptions for property owners who renovate existing or construct new buildings. CRAs are areas of land in which property owners can receive tax incentives for investing in real property improvements. The program is delineated into two distinct categories, those created prior to July 1994 (“pre-1994”) and those created after the law changes went into effect after July 1994. HB 123, sponsored by Representatives’ Mark Frazier and Jon Cross, will streamline the process of creating a new CRA by eliminating the requirement that the Ohio Development Services Agency approve a proposed CRA. The legislation:

- Extends the authority to designate a community investment area (CRA) to townships

that have adopted a limited home rule government;

- Eliminates the requirement for the Department of Development to approve a proposed

CRA;

- Requires the Department to prescribe a model CRA exemption agreement between

owners of a commercial or industrial project and local authorities;

- Increases, from 50% to 75%, the percentage of a proposed CRA exemption for a

commercial or industrial project that requires obtaining permission from a school

district encompassing the project;

- Modifies the requirement that municipalities share municipal income tax revenue

generated by new employees at a large CRA commercial or industrial project with the

school district encompassing that project;

- Reduces, from five to two years, the amount of time required to transpire between the

discontinuation of a CRA commercial or industrial project and when the project’s owner

may obtain an enterprise zone tax exemption or another CRA exemption;

- Removes the requirement that the owner of a CRA commercial or industrial project

notify the local authority in advance of relocating the site of the project to another local

authority’s CRA;

- Modifies the recipients of and the information appearing in a required annual report

issued by local authorities detailing CRA commercial and industrial projects; and

- Eliminates fees paid by CRA commercial and industrial project owners to the local

authority and the Department of Development to cover the cost of administering such

projects.

Tax Assessments. How property taxes are assessed is very important for the development of workforce housing. Illinois recently enacted Senate Bill 3895 that provides that assessed value for the residential real property in the base year means the assessed value used to calculate the tax bill, as certified by the board of review, for the tax year immediately prior to the tax year in which the building permit is issued, provides that for property assessed as other than residential property, the assessed value for the residential real property in the base year means the assessed value that would have been obtained had the property been classified as residential. The Ohio General Assembly passed a significant reform that will make sweeping changes to the state’s real property tax law. HB 126, once signed by Governor Mike DeWine in the coming weeks, will effectively end practices that have impacted Ohio property owners for years. Currently, Ohio school districts can challenge property values to increase the assessed value or fight property owners’ attempts to lower their assessed values. School districts can file complaints to make property owners pay more money in real estate taxes to increase the school district’s funding. Ohio is one of only a few states in the country that permits school districts to challenge the county auditor’s valuations. Additionally, according to WalletHub, Ohio has the 13th highest property taxes in 2022 with an average annual property tax of $2,271 on homes priced at the state’s median value. There has been growing concern among state representatives that by continuing to allow school districts to use these tactics, it would take away money from Ohio’s economy and funding for other taxing authorities and social service programs. HB 126 aims to fix this issue by changing the structure of Ohio real property tax valuation contests such as:

- Limiting the filing of property tax complaints by boards of education and other subdivisions to instances where (i) the property was sold in a recent arm’s length transaction in the year before the tax year for which the complaint is filed, (ii) the sale price of the property is at least 10% and $500,000 more than the auditor’s value, and (iii) the subdivision first adopts a resolution authorizing the complaint with notice sent to the property owner at least seven days before adopting the resolution. These limitations would end the practice of retroactive tax increases attributable to years in which a sale occurs. The $500,000 threshold also is indexed to increase each year with inflation.

- Ending private pay settlement agreements between a property owner and a board of education after the effective date of the bill. Currently, property owners would make a settlement payment to the board of education to dismiss, not file, or settle a complaint by agreeing to new value for the property that is not reflected on the tax list. HB 126 would also prohibit a subdivision’s standing to appeal a board of revision decision to the Board of Tax Appeals. Although the bill is silent on whether a subdivision could enter as an appellee in a BTA appeal from a BOR decision.

- Removing the requirement that school districts receive notice of a complaint.

- Modifying the timeline in which school districts can file a counter-complaint to 30 days after the initial complaint is filed. Currently, a school district may file a counter-complaint within 30 days after receiving notice of the owner’s complaint.

- Requiring that a county Board of Revision dismiss a complaint filed by a subdivision within one year after the complaint was filed if the Board of Revision does not render a decision within that timeframe.

HB 126 specifies that most of its changes will apply to complaints or counter-complaints filed for tax year 2022 and thereafter, except for provisions regarding private payment agreements which will apply on or after the bill’s effective date. The bill is expected to affect each property owner differently.

Tax Credits. State legislation is being introduced in Ohio and elsewhere to foster the development of workforce housing using state tax credits. Several pieces of state legislation have been introduced to impact the development of workforce housing and they are outlined briefly below.

- Ohio House Bill 470- Multi-Family Residential Housing legislation would authorize the Ohio community investor credit for qualifying developers of multi-family residential housing projects.

- Ohio House Bill 560- Affordable Rental Housing legislation would authorize a non-refundable tax credit for the construction or rehabilitation of affordable rental housing. At present, 22 other states (and growing) have effectively utilized state housing tax credit programs as a mechanism to provide a state level funding to draw down these federal resources to meet affordable housing needs. This bill will create an Ohio Workforce Housing Tax Credit leveraging the existing federal housing tax credit – the primary tool Ohio will utilize to drive creation of affordable workforce, family, and senior housing through private investment. In addition, this credit will have an immediate, profound economic development impact on Ohio communities’ years before the state issues the credit.

- Indiana Senate Bill 262- Housing Tax Credit legislation that would provide an affordable and workforce housing state tax credit against state tax liability to a taxpayer for each taxable year in the state tax credit period of a qualified project in an aggregate amount that does not exceed the product of a percentage between 40 and 100 percent and the amount of the taxpayer’s aggregate federal tax credit for the qualified project.

- Kansas Senate Bill 375- Housing Tax Credit legislation that would create the Kansas housing investor tax credit act, facilitates economic development by providing tax credits for investment in residential housing projects in underserved rural and urban communities to accommodate new employees and support business growth.

The state of Ohio offers a Transformational Mixed Used Development tax credit tied to the insurance premium tax that provides a $100 M in tax credits annually for four years to support large scale mixed used developments in urban markets as well as small mixed-use projects in non-major cities to ensure that rural communities can access to this funding.

States across the Union are very engaged in addressing the housing challenge through a wide range of programs, policy changes and outlining how local governments regulate land use and property tax assessments.

[i] See generally Gary L. Sullivan, Steve A. Johnson, and Dennis L. Soden, “Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Best Practices Study,” University of Texas at El Paso, September 2002.

[ii] See Rose Naccarato, “Tax Increment Financing, Opportunities and Concerns,” Staff Research Brief, Tennessee Agency on Intergovernmental Relations, March 2007.

[iii] How TIF Works: Basic Mechanics, Minnesota House of Representatives, House Research, http://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/issinfo/tifmech.htm.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.