The location of solar, wind and other renewable energy projects is a hot topic in many Ohio communities. Ohio has shifted decisions on state energy policy to local governments throughout the state. This shift puts millions of dollars in local government and school district funding in jeopardy. Energy companies and communities need to understand the critical role of local governments in approving renewable energy projects and the funding that is in jeopardy by local public officials bending to the Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) crowd.

Ohio provides different regulatory and tax incentive processes for renewable projects based on whether they are large or small scale, but local government officials play a critical role in gaining approval for these investments. The Ohio Revised Code defines a major utility facility as an electric generating plant with a capacity of 50 megawatts (MW) or more (including solar and wind energy facilities); an electric transmission line and associated facilities of 100 kilovolts (kV) or more; or a gas pipeline that is greater than 500 feet in length, more than nine inches in outside diameter, and designed for transporting gas at a maximum allowable operating pressure in excess of 125 pounds per square inch.[i] The statute defines economically significant wind farms as wind turbines and associated facilities with a single interconnection to the electric grid and designed for, or capable of, operation at an aggregate capacity of 5 or more MW but less than 50 MW.[ii] The term economically significant wind farm excludes one or more wind turbines and associated facilities that are primarily dedicated to providing electricity to a single customer at a single location that is designed for, or capable of, operation at an aggregate capacity of fewer than twenty megawatts, as measured at the customer’s point of interconnection to the electrical grid.[iii] Before construction can begin on any major utility facility or economically significant wind farm within the state of Ohio, a certificate of environmental compatibility and public need must be obtained from the Ohio Power Siting Board.[iv] However, recent legislation requires a large-scale solar facility to gain approval from the project’s county commissioners prior to gaining a certificate of environmental compatibility and public need (certificate) from the Ohio Public Siting Board. These large projects also require agreements to train and equip local emergency responders, as well as repair roadway infrastructure following the construction of the project.

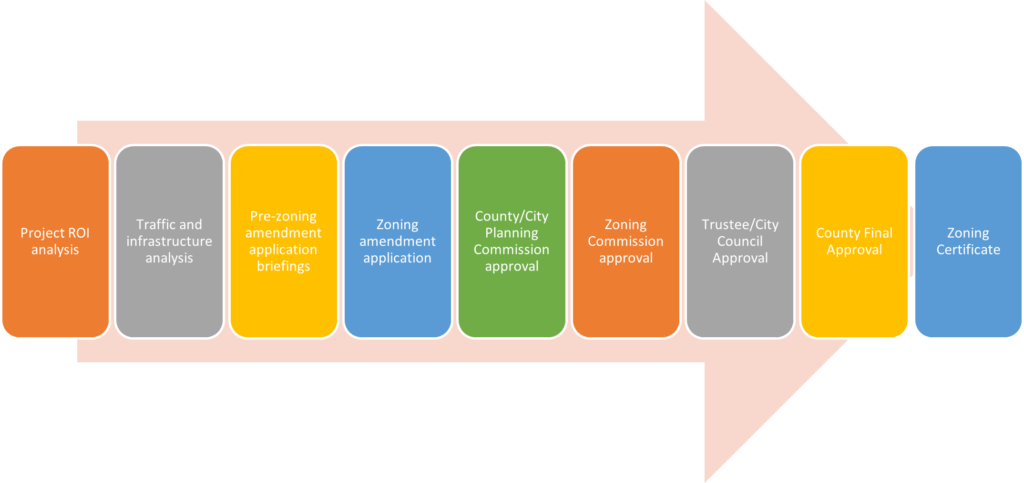

Small-scale solar projects, less than 50 MW, are exposed to the local zoning process in Ohio. Local governments manage design, growth, and development through the land use entitlement process typically through a comprehensive plan that can serve as a legally binding document that sets the overall goals, objectives, and policies to guide the local legislative body’s decision-making regarding the development of a region or community. Municipal or county planning commissions help guide growth and development and set the framework for zoning regulation. Their focus is the development of studies, maps, and plans that recommend planned uses for land based upon the physical, environmental, social, economic, and governmental characteristics, functions, services, and other aspects” of their geographic area, and the initial review of new zoning ordinances or amendments to existing zoning ordinances.[v] As an example, Ohio law permits townships to create zones of land uses, and regulate, consistent with their comprehensive plan, the location, height, bulk, number of stories, size of buildings, and other structures, including tents, cabins, and trailer coaches, percentages of lot areas that may be occupied, set back building lines, sizes of yards, courts, and other open spaces, the density of population, uses of buildings and other structures, including tents, cabins, and trailer coaches, uses of land for trade, industry, residence, recreation, or other purposes in the unincorporated territory of the county, and landscaping and architectural standards (excluding exterior building materials in the unincorporated territory of the county. [vi] Ohio cities and townships may adopt a prohibition of renewable energy projects such as solar and wind facilities through there zoning codes, but those codes can be amended.

Notice is then provided to all persons mandated by the zoning ordinance/resolution, mailed to the tax mailing or street addresses, through publication in a newspaper of general circulation, or posting a sign(s) on the property. Once the zoning application is received by the zoning official, the staff reviews it for accuracy and completeness, and a hearing is held before a regional planning commission. A written recommendation to the jurisdiction’s planning commission is then created, and ultimately a vote is taken on the zoning by the city council or township trustees. However, in many jurisdictions, the citizens still retain the right to place a referendum on the ballot to overturn the zoning action by the city council. Zoning is a democratic process. Even though local government officials vote to award a zoning change to the site and followed all the required regulations in the process of making that change, the voters can challenge zoning amendments. Judicial review of the local government zoning decision will require the trial court to weigh the evidence in the record and whatever additional evidence is admitted pursuant to state law to determine whether a preponderance of the reliable, probative, and substantial evidence exists to support the agency’s decision. For utility-scale solar projects, Ohio law indicates that a project with an Ohio Power Siting Board certificate will preempt any specific zoning challenges. Thus, solar projects larger than 50 MW are pre-empted from local zoning prohibition but still must gain the local county commissioner’s approval for their project as part of the Ohio Power Siting Board process.

Ohio, like many other states, offers economic development incentives in exchange for renewable energy investments. One example is Ohio’s Qualified Energy Project Tax Exemption offered through the Ohio Department of Development (ODOD) pursuant to Ohio Revised Code (ORC) § 5727.75.[1] However, the Ohio General Assembly has created a multi-tiered governmental approval process for the Qualified Energy Projects to come to life. The Ohio Qualified Energy Project program provides owners or lessees of “qualified energy projects” with an exemption from the public utility tangible personal property tax if it meets certain criteria as certified by the Ohio Director of Development. The Qualified Energy Projects will remain exempt from taxation so long as the project is completed within the statutory deadlines, meets the “Ohio Jobs Requirement,” and continues to meet several ongoing obligations including providing ODOD with project information on an annual basis. A qualified energy project includes any renewable energy resources as defined in the state’s renewable portfolio standard as well as clean coal, advanced nuclear, and co-generation.[2]

Tax exemptions are a great opportunity for companies to develop renewable energy projects while eliminating some of the costs that come with them. It is also a great opportunity for communities and their school districts to receive more money than these properties generate via tax dollars before the development. Small Qualified Energy Projects (less than 250 kilowatts) are exempt as a matter of law pursuant to ORC § 5709.53 from gaining approval from the county commissioners; however, these projects will not progress unless a tax abatement is provided that is awarded by the local county commissioners. Thus, Ohio county commissioners do control the future of even small-scale renewable projects. Approval of the county commissioners involves the negotiation of a PILOT payment that can range from $7000 to $9000 per MW for the life of the project.

The Ohio Qualified Energy Project program provides a substantial funding opportunity for Ohio’s schools and local governments. Ohio’s property taxes fund local schools, developmental disabilities services, children’s services, emergency medical services, health services, senior services, community colleges, cities, villages, townships, and counties. However, for property tax purposes, farmland devoted exclusively to commercial agriculture may be valued according to its current use rather than at its “highest and best” potential use. This provision of Ohio law is known as the Current Agricultural Use Value (CAUV) program. By permitting values to be set well below true market values, the CAUV normally results in a substantially lower tax bill for working farmers, but it also can dramatically impact the revenue collected for local governments and school districts. In essence, this substantial tax break provided to farmers takes funding away from those entities dependent upon the property tax to operate. However, Ohio’s Qualified Energy Project program provides a tool for local governments to address this challenge through a Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) based upon the development of renewable energy Ohio projects. The table below illustrates the local government revenue gains from even a $7000 per MW PILOT payment.

| Distribution of 49.9 MW Renewable PILOT | ||||

| Local Government Agencies | Percentage | Current Taxes | PILOT | Revenue Gain |

| County General Fund | 6.29% | $261.80 | $21,959.79 | $21,697.99 |

| County Children Services | 2.95% | $122.72 | $10,293.87 | $10,171.15 |

| County Developmental Disabilities | 5.89% | $254.44 | $20,587.39 | $20,341.96 |

| County Emergency Medical Services | 4.91% | $204.53 | $17,156.22 | $16,951.69 |

| County Health Department | 1.57% | $65.45 | $5489.94 | $5424.50 |

| County Senior Citizens | 1.96% | $81.80 | $6862.34 | $6870.34 |

| Community College | 1.96% | $81.81 | $6,862.35 | $6,780.54 |

| County Subtotal | 25.54% | $1,063.57 | $89,212.27 | $88,148.70 |

| City School District | 57.56% | $2,397.12 | $201,070.70 | $198,673.58 |

| Joint Vocational District | 3.93% | $ 163.63 | $13,725.04 | $13,561.42 |

| Township General Fund | 3.14% | $130.90 | $10,979.90 | $10,849.00 |

| Township Road and Bridge | 1.96% | $81.81 | $6,862.35 | $6,780.54 |

| Township Cemetery | 1.96% | $81.81 | $6,862.35 | $6,780.54 |

| Township Fire | 5.89% | $245.44 | $20,587.39 | $20,341.95 |

| Township Subtotal | 12.97% | $539.97 | $45,292.33 | $44,752.37 |

| PILOT Total | 100% | $4,164.28 | $349,300.00 | $345,135.72 |

This hypothetical renewable energy project would create 49.9 MW of power at a site that currently only provides $4,164.28 of property taxes due to the CAUV tax exemption but would generate $349,000 annually for the life of the renewable energy project through a $7000 per MW PILOT payment. Ohio’s decision to let local governments decide whether renewable energy projects happen in their community is not only an unwise delegation of the state’s energy policy but can cost children, seniors, public safety, economic developers, and the public every time local government officials respond to the opposition of area residents.

Please contact Dave Robinson at [email protected] for assistance with any renewable energy project or other economic development matters.

[1] https://development.ohio.gov/business/state-incentives/qualified-energy-project-tax-exemption#:~:text=The%20Qualified%20Energy%20Project%20Tax,utility%20tangible%20personal%20property%20tax.

[2] https://codes.ohio.gov/ohio-revised-code/section-5727.75/7-21-2022

[i] Ibid.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] https://opsb.ohio.gov/about-us

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.