Five million Americans have simply left the workforce since COVID-19. That is the size of the state of Alabama and a bigger group of people than the population of every American city except for New York City. In fact, In 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), over 47 million Americans voluntarily quit their jobs — an unprecedented mass exit from the workforce, spurred on by Covid-19, that is now widely being called the Great Resignation.

According to the BLS, a little over a year after the COVID-19 pandemic began, economists and other observers took note of a rising job quit rate, as measured by the BLS Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) program. JOLTS recorded a seasonally adjusted quit rate of 2.4 percent in the second month of the program’s existence (January 2001), and although this level was matched at other times, it was not surpassed until March 2021, when the quit rate reached 2.5 percent. This new record was quickly eclipsed in April 2021, when the quit rate stood at 2.8 percent; the current record is 3.0 percent, first reached in November 2021 and matched in December 2021.

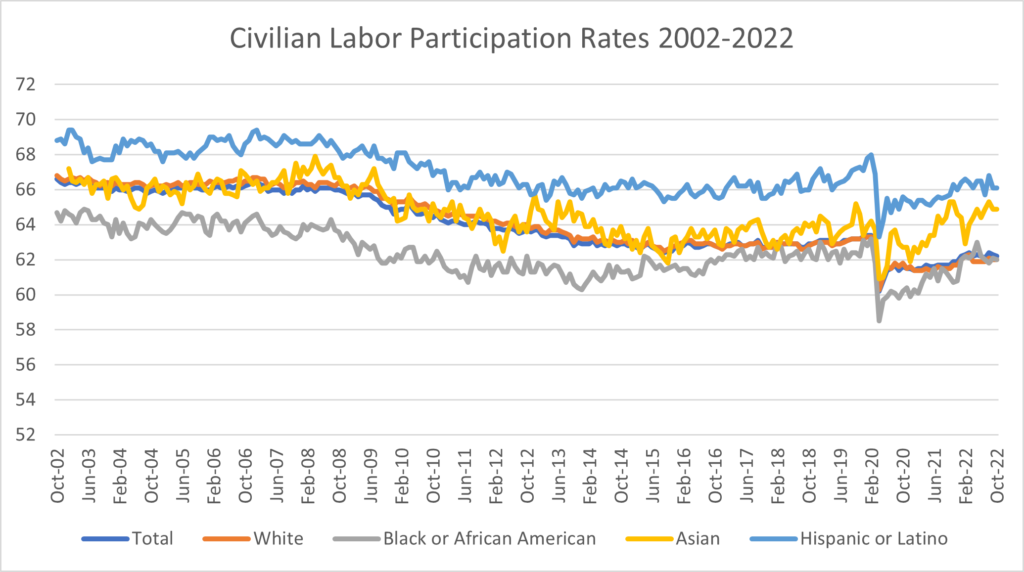

Civilian Labor Participation rates, the prime measure by the federal government of how many Americans are active in the workforce, has not recovered to pre-pandemic rates as illustrated by the chart below. The U.S. Civilian Labor Participation rate is 1.2 points lower than prior to when COVID-19 began to impact the economy in February of 2020.

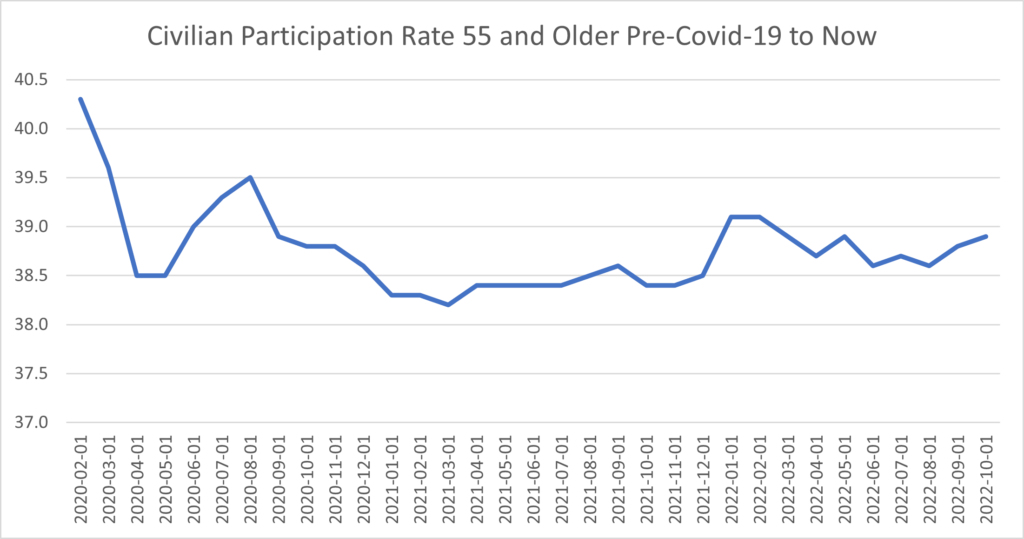

As of the third quarter of 2021, 50.3% of U.S. adults 55 and older said they were out of the labor force due to retirement, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of the most recent official labor force data. In the third quarter of 2019, before the onset of the pandemic, 48.1% of those adults were retired. In regard to specific age groups, in the third quarter of 2021 66.9% of 65- to 74-year-olds were retired, compared with 64.0% in the same quarter of 2019.

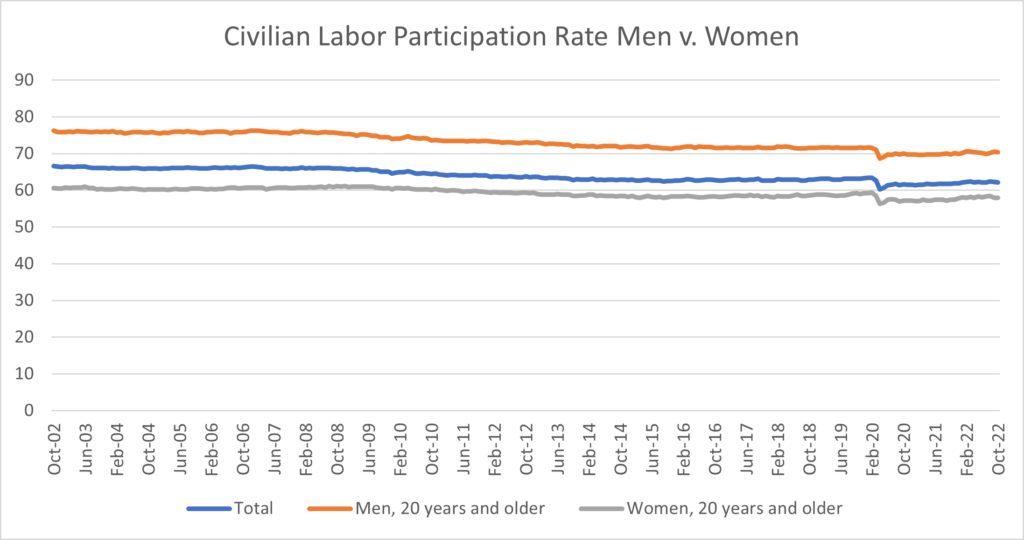

COVID-19 enhanced the impact of the lack of available childcare driving more women primarily to leave the workforce. Women over 20 years of age civilian labor participation rate is at 58% which is 1.3 % lower than prior to COVID-19 impacting the economy in February of 2020 as the chart below illustrates.

A report from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation and The Education Trust found that the pandemic created a vicious cycle for the industry; to return to work, workers need reliable childcare, but providers are facing immense challenges themselves. The pandemic forced many childcare providers to close or scale down: between February and April 2020, the industry lost 370,600 jobs — 95% of which were held by women. Unfortunately, the recovery has not been swift; as late as September 2021, childcare industry employment remained 10 percent lower than pre-pandemic levels.

Why did the Great Resignation happen? A recent Harvard Business Review article identified five factors, exacerbated by the pandemic, which they termed the Five R’s to include retirement, relocation, reconsideration, reshuffling, and reluctance.[i] Workers are retiring in greater numbers but aren’t relocating in large numbers; they’re reconsidering their work-life balance and care roles; they’re making localized switches among industries, or a reshuffling, rather than exiting the labor market entirely; and, because of pandemic-related fears, they’re demonstrating a reluctanceto return to in-person jobs.

At the peak of the Great Resignation in July of 2021, employees between 30 and 45 years old had the greatest increase in resignation rates, with an average increase of more than 20% between 2020 and 2021. A Harvard Business Review study found that from 2020 to 2021, resignations decreased for workers in the 20 to 25 age range. Interestingly, resignation rates also fell for those in the 60 to 70 age group, while employees in the 25 to 30 and 45+ age groups experienced slightly higher resignation rates than in 2020. Can you say “Zoom Fatigue”? Clearly, the shift to remote work was a challenge for many workers. This same HBR study found resignation rates were higher in the health care and tech fields based upon pandemic demand increases.

Enhanced unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, and not being able to go out and spend money during the COVID -19 lockdown all contributed to Americans collectively adding $4 T to their savings accounts since early 2020. The extra few hundred dollars a week from enhanced unemployment benefits (which ended in Sept. 2021), specifically, led to 68% of claimants earning more on unemployment than they did while working according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. In the U.S. Chamber’s Nov. 2021 survey, 28% of women cited others in the family making enough money that working full-time is not as critical as the reason they have not re-entered the workforce. Just 17% of men said the same. Higher-income and savings bolstered people’s economic stability—allowing them to continue sitting out of the labor force. Losing several million workers in a labor shed as large as the United States of America would not typically be that big of an issue. However, the retirement of the very large Baby Boom generation and the failure of younger generations to successfully fill this workforce gap has created nearly 11 M open jobs in the U.S.. The Great Resignation hit right at the wrong time and millions of Americans are likely not to rejoin the workforce.

[i] The Great Resignation Didn’t Start with the Pandemic, Harvard Business Review, Joseph Fuller and William Kerr, March 23, 2022.