Chasing megaprojects is the headline of 2022. EV and computer chip factories offer billion-dollar investments and Governors across the nation are spending billions of dollars to lure these companies to their states. Movie junkies who will remember a young Robert Redford in the 1972 movie “The Candidate” starring as an unlikely and then successful candidate for the U.S. Senate who stunned and in route to a victory speech pulls his campaign manager, Peter Boyle, into a closet and in a panic says, “What do we do now?”. Many communities who hunt and then catch a megaproject such as a micro processing chip manufacturer or EV battery plant find themselves asking the same question from a workforce development standpoint.

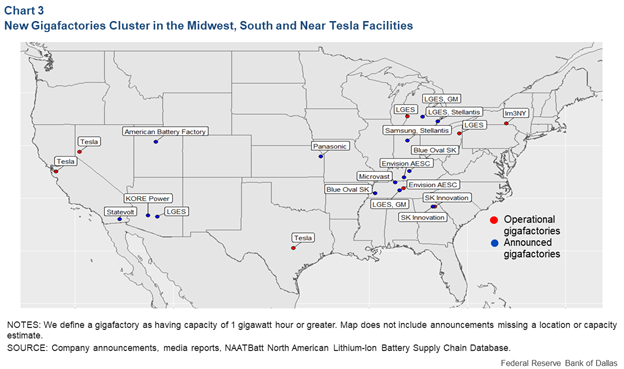

Megaprojects are on the rise in the United States driven primarily by the computer chip fab plants and the transition of the global automobile industry from the internal combustion engine to electric vehicles. The map above from the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank outlines a list of EV battery projects that have been announced—this list grows every week and does not include recent announcements such as the Honda-LG project in Ohio. In a market that has lost millions of workers and has over 10 M open jobs in the United States, megaprojects can provide substantial stress on an already struggling workforce development market.

What do you do now? Communities fortunate enough to land megaprojects are likely selected based on the availability of a site that has a pool of available workers. Markets like Detroit have an existing workforce in the internal combustion engine (ICE) industry of 180,000 workers. All these jobs are at risk in a new EV automobile marketplace. No more transmission or engine plants that dot the countryside across the U.S.. While this is a frightening proposition, existing ICE workers are prime candidates to work in new EV battery facilities. Retraining of existing workers is a prime tool for addressing the workforce challenge created by megaprojects in the EV marketplace.

Addressing the workforce challenge created by the location of a computer chip Fab facility is more complicated. Community college partnerships are likely the answer for addressing the computer chip megaproject. Arizona offers a successful model. Intel has 11,000 employees in Chandler, Arizona, and a supply chain extends through the Phoenix urban marketplace. Regional community colleges have stepped in to fill the tech manufacturing workforce gap. The Chandler-Gilbert Community College (CGCC) is one of three colleges in the Maricopa County Community College District to offer a Semiconductor Technician Quick Start program, an in-person, 10-day certification course where participants can learn the skills needed to join this fast-growing industry—in less than two weeks. Estrella Mountain Community College and Mesa Community College are offering the program as well, developed in partnership with major area employers such as Intel Corp. The Semiconductor Technician Quick Start program can be completed at no cost to Arizona residents. Those meeting the eligibility will receive a $270 tuition stipend, fully covering Maricopa County resident tuition—and partially covering non-resident tuition, and this stipend is awarded upon successfully completing the class and passing the NIMS Technician Certification test. Students who do not pass the certification test will be responsible for paying the $270 tuition. Of course, Phoenix has another advantage— population growth. Based largely on migration from California and Snowbirds, Phoenix has grown from 1.4 M people to 4.5 M since Intel invested in the market in 1980. This dramatic population increase answers many workforce development challenges.

The impact of megaprojects on a region and state’s existing industries is a larger concern. These new jobs are jumping into a crowded labor market and are likely to “rob Peter to pay Paul” by taking workers from existing companies. Local and state economic development leaders need to build flexibility into their economic development incentive and workforce development programs to focus more on job retention, capital investment, and workforce training for projects that may not create a net, new jobs. In fact, these companies losing workers are likely going to be forced to automate more of their tasks if possible.

Megaprojects are a prime focus for communities and states across the United States seeking to not be left behind as major industries transition or to capitalize on the back-shoring of critical supply chain products. However, these same communities and states need to recognize that the law of unintended consequences always applies, and they need to adapt their economic development incentive programs to retain existing employers seeking to survive the megaproject tsunami.