The redevelopment of neighborhoods impacted by vacant housing is a challenge for urban, suburban, and rural communities alike. Housing redevelopments can be a critical placemaking initiative in small and big towns alike. The International Economic Development Council has defined placemaking as “the practice of enhancing a community’s assets to improve its overall attractiveness and livability.” Placemaking is defined as large-scale projects like the creation of new public or revitalized public spaces, alternative transportation infrastructure, pop-up retail, housing development, or Downtown beautification projects. Bike trails, public beer gardens, parks, and other public spaces often mix uses and are attractive to residents and visitors alike. However, successful placemaking strategies require the use of multiple tools as well as an overall improvement in the quality of life available to area residents and visitors.

Five tools drive placemaking economic development strategies that transform communities, including:

- Historic preservation redevelopment.

- Parks and trail development.

- Landbanks that spur housing redevelopment.

- Housing development; and

- Economic development incentives drive Downtown district redevelopment.

Land banks are quasi-governmental entities with unique powers, created pursuant to state-enabling legislation, that are solely focused on converting problem properties into productive use according to local community goals.[1] Vacant, abandoned, and tax-delinquent properties are typically considered problem properties because they destabilize neighborhoods, create fire and safety hazards, drive down property values, and drain local tax dollars. Land banks were created as a direct response to a growing trend of problem properties to strategically acquire them, rehabilitate them, and transfer them to new owners in a manner that aligns with community-based plans. These programs can also be developed within existing entities, such as redevelopment authorities, housing departments, or planning departments. Land banks have special powers that enable them to undertake these problem properties far more effectively and efficiently than other public or nonprofit entities including the power to: (i) acquire property through various mechanisms such as the tax foreclosure process; (ii) hold title to tax exempt property and extinguish back taxes; (iii) clear title; (iv) consolidate and assemble publicly held inventory into a single agency/department; (v) streamline disposition and sale of properties to responsible owners or developers, (vi) lease properties for temporary uses; and (vii) convey property for below market value, focusing on an outcome that best aligns with future land use goals, rather than the highest bid price. County land banks can acquire low-value properties and demolition funding from lending institutions (including Fannie Mae) and receive low-value property transfers from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, private developers, and probate estates.[2] Additionally, the county land bank can borrow money, receive money through land sales, and obtain funds as a state or federal grant applicant or co-applicant. When thoughtfully executed, land banks can resolve some of the toughest barriers to returning land to productive use, helping to unlock the value of problem properties, and converting them into assets for community revitalization. A common misconception is that land banks compete with the private market. Contrarily, land banks remedy the growing inventory of problem properties the private market has altogether rejected. Most vacant and abandoned properties have serious legal and financial barriers, such as clouded title, that detract private investors. Also, many tax-foreclosed properties have accumulated years of back taxes that far exceed the market value of the property. Similarly, many properties left vacant and abandoned for years require an investment in repairs that greatly exceeds what the market could ever return. A land bank, therefore, is designed specifically to address the inventory of problem properties the private market has discarded, and to convert these neighborhood liabilities into valuable assets for the good of the community. However, land banks are not a “silver bullet” for communities struggling with vacant, abandoned, and deteriorated properties. Communities must also have other strategies and activities, such as strategic code enforcement, smart planning and community development, and effective tax collection and enforcement to remedy problem properties.

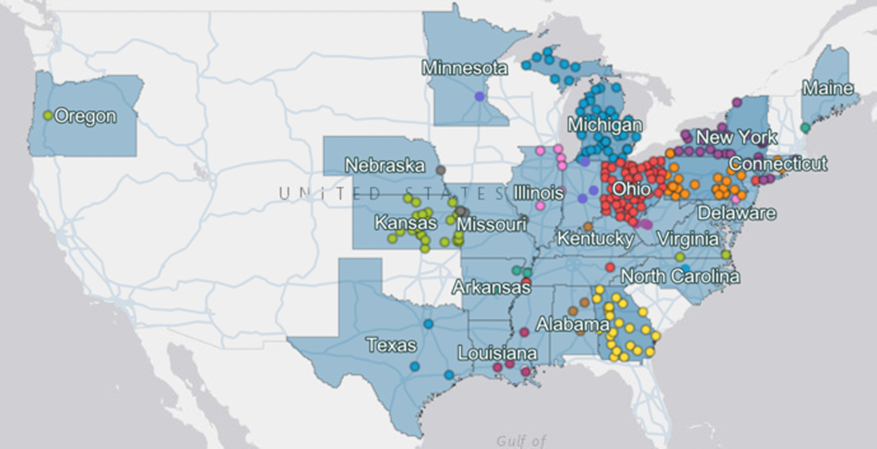

There are currently more than 250 land bank programs in 17 states—most of them existing in Michigan, Ohio, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and New York.[3]

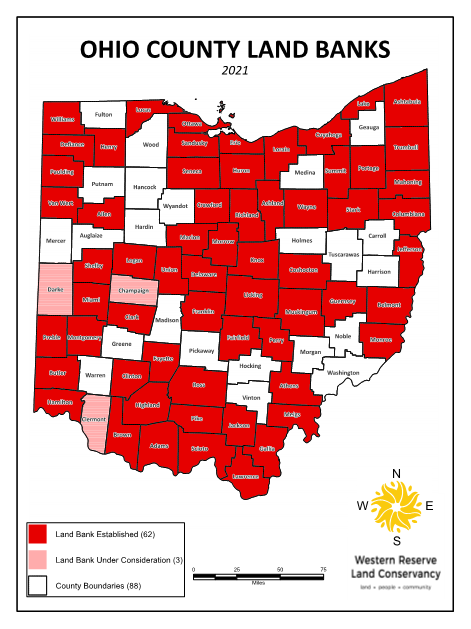

As of 2021, 62 of Ohio’s 88 counties have land banks. [1] These programs have been launched in a range of communities, such as “Legacy Cities”—those former industrial cities suffering from decades of disinvestment and population loss—and suburban and rural towns hit hard by the mortgage foreclosure crisis. One notable community in Ohio that has really benefited from land banks is Butler County. In the last decade, the Butler County Land Bank has spent $7.8 million in rehabilitating and reutilizing 1,000 properties.[2] This land bank works with almost all its municipalities— except Monroe, College Corner, and Sharonville. Butler County used Moving Ohio Forward money and the Neighborhood Initiative Program to fund these projects which primarily targeted Hamilton and Middletown. In 2014, the total value of the targeted neighborhoods was $526 million in Hamilton and $81.8 million in Middletown. In 2020, the total value increased to $667 million in Hamilton and $120.6 million in Middletown; a 27% increase and 47% increase in each municipality, respectively. Middletown police calls also dropped 44% from 2016 to 2020, overdose runs decreased 51% and fire calls were down 6%. In Hamilton, vacant house fires dropped 62%. On Feb. 18, Butler County Land Bank Executive Director Seth Geisler submitted 51 projects totaling about $11.5 million to the state. The bulk of the money would go to razing the former Forest Fair Mall as well as demolishing 26 Hamilton properties, 15 Middletown properties, 4 others from Fairfield and one each from New Miami and Lemon, Liberty, Ross, and St. Clair townships. Geisler says land banks are a great opportunity for private investors because the property remains tax-free if the land bank holds the title which could be used as an incentive for public sector-private sector partnerships.

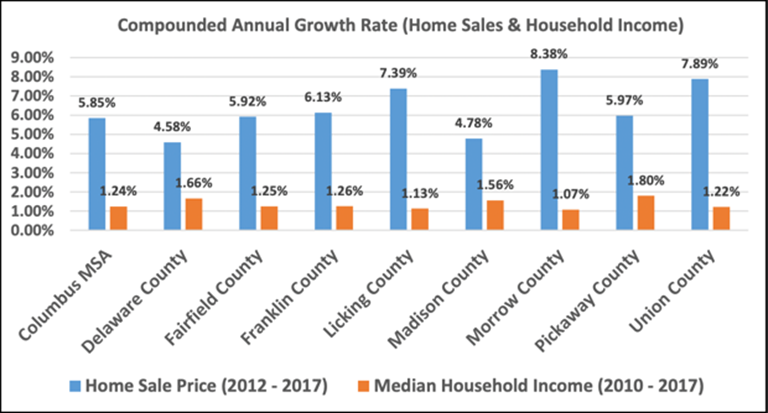

The national average for property tax delinquency rates has declined from 7.1% in 2011 to 5.9% in 2021.[1] However, Ohio has consistently seen a greater percentage of delinquent properties than the national average throughout the last decade. Ohio peaked at 8.9% in 2013 and currently has a 6.6% delinquent property rate, or 0.5% higher than the national average. These statistics indicate a problem for the state of Ohio as, in addition to the delinquent property rate, some of its Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) have seen a faster rate of population growth and workforce demand than housing development. Columbus, for example, needs additional supply. This is evident by the rapidly escalating prices for homes and apartments. What’s been less clear is the extent to which the area may be underbuilding, in which communities and price points, and how the situation may play out over the coming decades. The new Housing Need Assessment report from the Building Industry Association of Central Ohio and the BIA Foundation quantified the significance of the shortfall by estimating the need for new residential housing based on projected job growth through 2050. These findings are concerning. Essentially, Central Ohio must build more than 14,000 housing units per year to accommodate an estimated 500,000 new jobs and 1 million new residents by 2050. The area is currently building about 8,000 housing units per year, meaning there is a shortfall of about 6,000 units, or 43%. The report also examined permitting activity for buildings in the peer markets of Charlotte, Nashville, and Austin. The results conclude that homes and apartments are being built at a much faster rate in those regions to accommodate their own rapid growth projections. In Columbus, the compounded annual growth rate in home price is nearly five times the compounded annual growth rate in the median household income. These trends will further exacerbate affordability housing challenges in the Columbus region and will limit the Columbus market from realizing job growth projections. If Columbus aims to be competitive as an appealing place to live and do business, it must have more affordable housing available to support residents.

The median home sale prices have far outpaced the median household income growth on the outskirts of the Columbus MSA Ohio as well due to high demand and low supply in the area.[2]

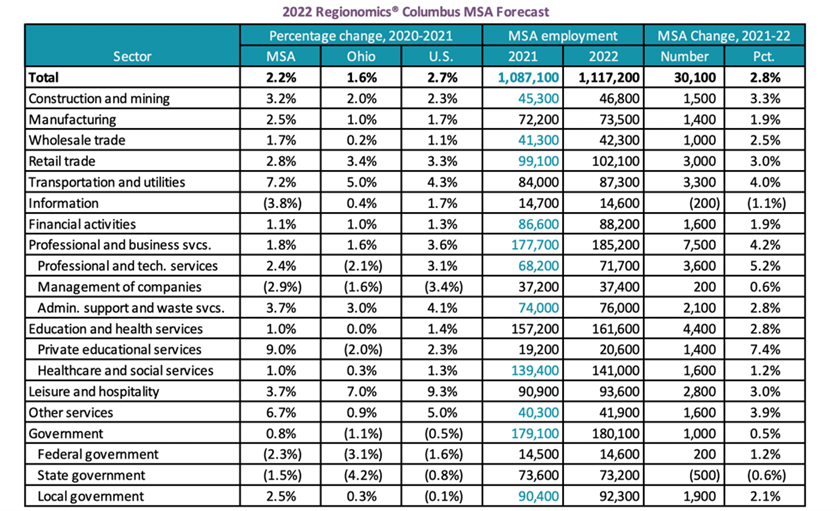

Predictions are that the U.S. and Columbus MSA employment will return to pre-pandemic levels in 2022. The two key uncertainties are the course of the pandemic and the number of workers returning to the labor force. As currently estimated, Columbus MSA employment grew 23,200 (2.2%) in 2021. This includes Regionomics adjustments to preliminary Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) employment estimates in many sectors. [1] This number will continue to grow especially because of the new Intel factory in New Albany which is estimated to create 7,000 construction jobs and 3,000 permanent positions.[2] Central Ohio needs to come up with a way to create more affordable housing at a faster rate or else miss out on other opportunities for economic development. Land banks are a great solution to help supplement housing development in an economically efficient and effective way so Columbus can remain competitive.

Please contact Dave Robinson at [email protected] if you are considering utilizing a land bank for redevelopment efforts.